Rebuilt Cable Bridge Across the Salmon River is One of Only Seven of its Kind in the World

The new suspension-cable Manning Crevice Bridge that crosses the pristine Salmon River above Riggins is nearly complete.

RIGGINS – All that remains of a cable suspension bridge that spanned the narrow, rocky Salmon River canyon east of Riggins for more than 80 years are two concrete abutments and a pair of skeletal steel arms, reaching outward from the granite cliff like a spurned lover.

In its place is a state-of-the-art 300-foot-long asymmetrical suspension bridge – one of only seven like it in the world. An 80-foot-high tower on the north side of the river holds six wound steel cables 3 inches thick that swoop down from the sky and grip the south side of the canyon. The cables are bored 125 feet down into the granite and held in tension to brace the steel-and-concrete deck, which is solid enough to support loaded logging trucks, farm machinery and river rafting excursions.

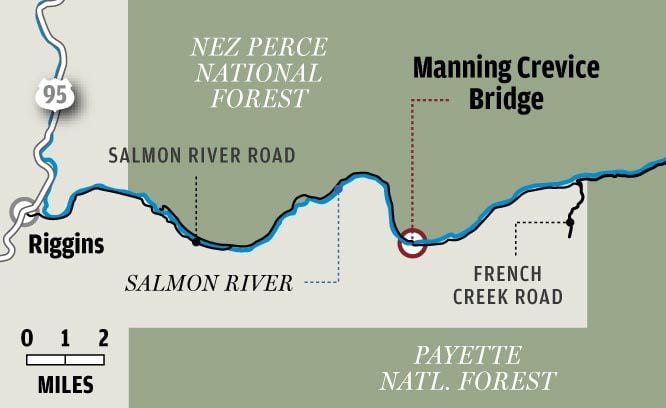

The $9.6 million Manning Crevice Bridge, set to be completed by the end of April, replaces the Depression-era link that employed scores of destitute young men and claimed the life of one during its construction. It sits 14 miles east of Riggins on the Salmon River Road, which ends five miles beyond the bridge at Vinegar Creek.

‘Quite a bridge’

“I think we got a good product, and I think the taxpayers got a good bang for their buck,” said Mike Dance, construction inspector for the contractor, Record Steel and Construction Inc., of Boise. “A really good bang for their buck.”

Work on the new bridge began two years ago, following negotiations with Idaho County officials over federal stipulations that, once the work is completed and paid for, the county will take over ownership and responsibility for future maintenance. County officials balked at first, fearing if major repairs are needed in the future, the county would not have the money to pay for it.

But the old wooden tower bridge, built in 1934 by the Civilian Conservation Corps, had passed its prime and posed safety concerns.

Idaho County Road Supervisor Gene Meinen said there was no way to test the anchor strength on the old bridge, owned by the U.S. Forest Service, and acknowledged the replacement had to be done. The transfer of ownership from the federal government to the county was the only way the deal could be sealed, and county officials finally acquiesced.

Mike Cook, a former Forest Service road supervisor and currently a liaison for the county commissioners, agreed the new bridge is a benefit to the county.

“We agreed way back when to go ahead with the project, because it was the best thing for the citizens of Idaho County,” Cook said. The county commissioners “didn’t really want (to own) a bridge, but with the funding it was the only way it was going to happen.”

Cook said he’s kept an eye on the progress of the new Manning Crevice Bridge and is satisfied with the work. He also said the contractor finally kept its word to the county to remove a huge boulder perched on the cliff above the new bridge. County officials feared the boulder might someday break loose and crash down into the roadway, but the contractors balked at removing it, doubting the boulder was dangerous.

“We got a good project; we got a good product from the (Federal Highway Administration that provided the funding),” Cook said. “I’ve kept in pretty close contact and looked at it several times myself. It’s actually quite a bridge there; certainly different from the old one.”

An ambitious project

The old 248-foot-long Manning Crevice Bridge was built in 1934 by the Civilian Conservation Corps as part of an ambitious project to construct a highway through north central Idaho linking Riggins with the town of Salmon.

The project was promoted by Idaho businesspeople, landowners, miners, politicians and developers who wanted to save time and money moving goods and services from one side of the state to the other.

According to research on the CCC by Ivar Nelson, of Moscow, and Patricia Hart, an associate professor of history at the University of Idaho, camps were set up near Riggins and North Fork in the eastern part of the state where the men lodged while digging, blasting and carving their way through the Idaho wilderness toward a meeting point.

On the western side, three bridges were built across the river. The farthest and now the most famous was the Manning Crevice Bridge.

The cable suspension bridge was named after John C. Manning, one of the corps workers who drowned in the river during construction. The structure was built with creosoted timbers and concrete abutments. According to U.S. Forest Service documents, expenditures for the bridge in 1935 were $18,065.

Although the Salmon River Highway began in an atmosphere of optimism it soon ran into a number of roadblocks that eventually scuttled the plan.

Resistance to building a highway through Idaho’s pristine backcountry began to mount, Nelson said, even though environmentalists had not had much clout until then.

“It represents so many of the debates today,” he said. “There was a struggle nationally between wilderness advocates like Bob Marshall and Aldo Leopold, who wanted to preserve wilderness untouched. On the other hand, you had people who wanted to develop. And so that was the conflict.”

Not only were the country’s policymakers divided, but the Forest Service’s regional offices in Ogden, Utah, and Missoula, Mont., also disagreed about what to do with the proposed highway.

Meanwhile the boys of the CCC were working their way upstream when they began to run into sheer rock cliffs.

Work began grinding to a halt as crews had to blast more rock and barge materials and equipment to make headway.

The country also was in the midst of a buildup for World War II, which, when the U.S. entered the conflict in 1941, prompted Congress to disband the CCC and move many of the workers into military service.

“The road stopped, and that’s where it is today because after the war there was no support,” Nelson said. “The financial support to put it through did not exist.”

The road now ends about five miles east of the Manning Crevice bridge at Vinegar Creek.

Rare design

The old Manning Crevice bridge was a monumental achievement of its time, but it had drawbacks for the loggers, ranchers and recreationists who used it.

The old bridge went almost straight across the river, creating nearly 90-degree turns from the road to the approaches on either side that were often difficult for larger vehicles to maneuver.

Dance, the construction inspector, said bridge users will appreciate the new design that spans the river at more of a diagonal.

“Well, everybody that’s going to come up here is going to enjoy it because they don’t have that tight corner,” Dance said. “That old bridge, that was such a tight corner that a lot of people got stuck right there. In the old days they had little rails on the side, and they would grease them so when the tires hit them they would just slide.”

Dance said the new bridge has a single cable tower rather than one on each side of the river because of the narrowness of the rocky canyon and the potential for rock slides to come down and wipe out a second tower. There are only six other single-tower cable suspension bridges in the world, he added.

The two old wooden towers have been removed, but were not destroyed. One, standing about 40 feet high, was moved upriver about four miles and placed at the Cook Ranch.

The second was trimmed down several feet and installed at the entrance to Riggins City Park along U.S. Highway 95, which serves as the tiny town’s main street.

Jake Morrison, foreman for the construction crew, said it’s taken up to 20 people working on shifts for two years to complete the new bridge. There have been no major problems or injuries during the process, Morrison said, and people using the road have been cooperative and friendly even when traffic was delayed.

They also have been amazed.

“They’re pretty shocked how big it is compared to the old one,” Morrison said.

Finishing touches

Work is expected to be mostly wrapped up within a week or so. The crews will take a short break and return at the end of April to finish paving the approaches to the bridge and place a resin protective cover on the bridge deck.

“I like it up here,” Morrison said. “It’s definitely a nice spot to work. The winter wasn’t that bad. But it gets hot in the summer, especially this north side with the rocks and the heat radiating off it.”

Diann DiMaggio has worked on the project since its beginning, both as a traffic controller and a forklift operator.

As she has watched the new bridge come into place, DiMaggio said she has wondered about the workers who toiled to build the old bridge decades ago.

“I often thought how hard it would have been for them to do it,” she said. “Most of what they did was by hand. Holding it together was quite amazing.”

DiMaggio glanced over at the new structure and said she had mixed feelings about seeing the work come to completion.

“I’m going to be sad when it’s done,” she said. “I’m going to miss this place. But it’s time. It’s time to go on; it needs to be done.”

—

Hedberg may be contacted at [email protected] or at (208) 983-2326.